8.15. SQLAlchemy ORM About

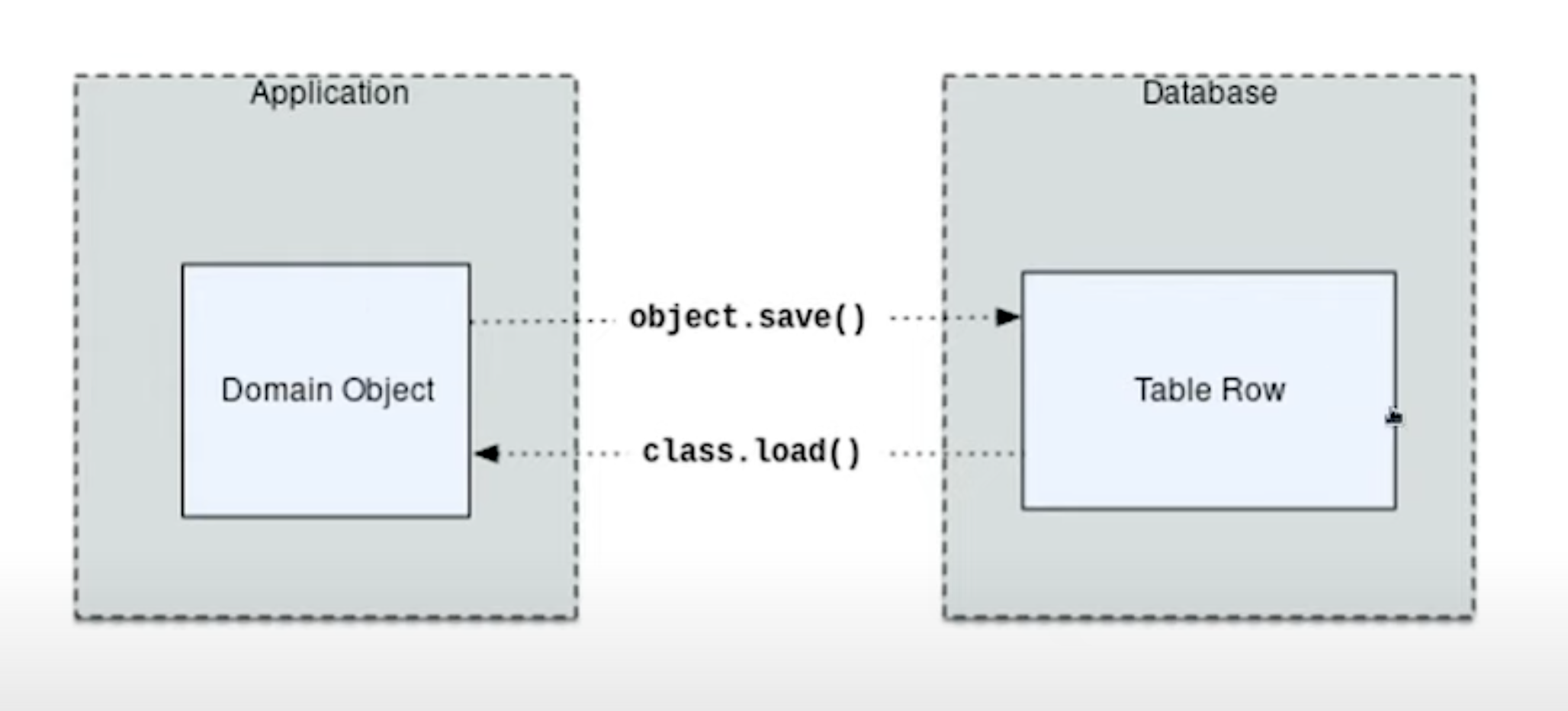

ORM - Object Relational Mapping

Process of associating object oriented classes with database tables

Set of object oriented classes is a domain model (business model)

The most basic task is to translate between domain object and a table row

Any tool which takes database row and converts this to an object is an ORM

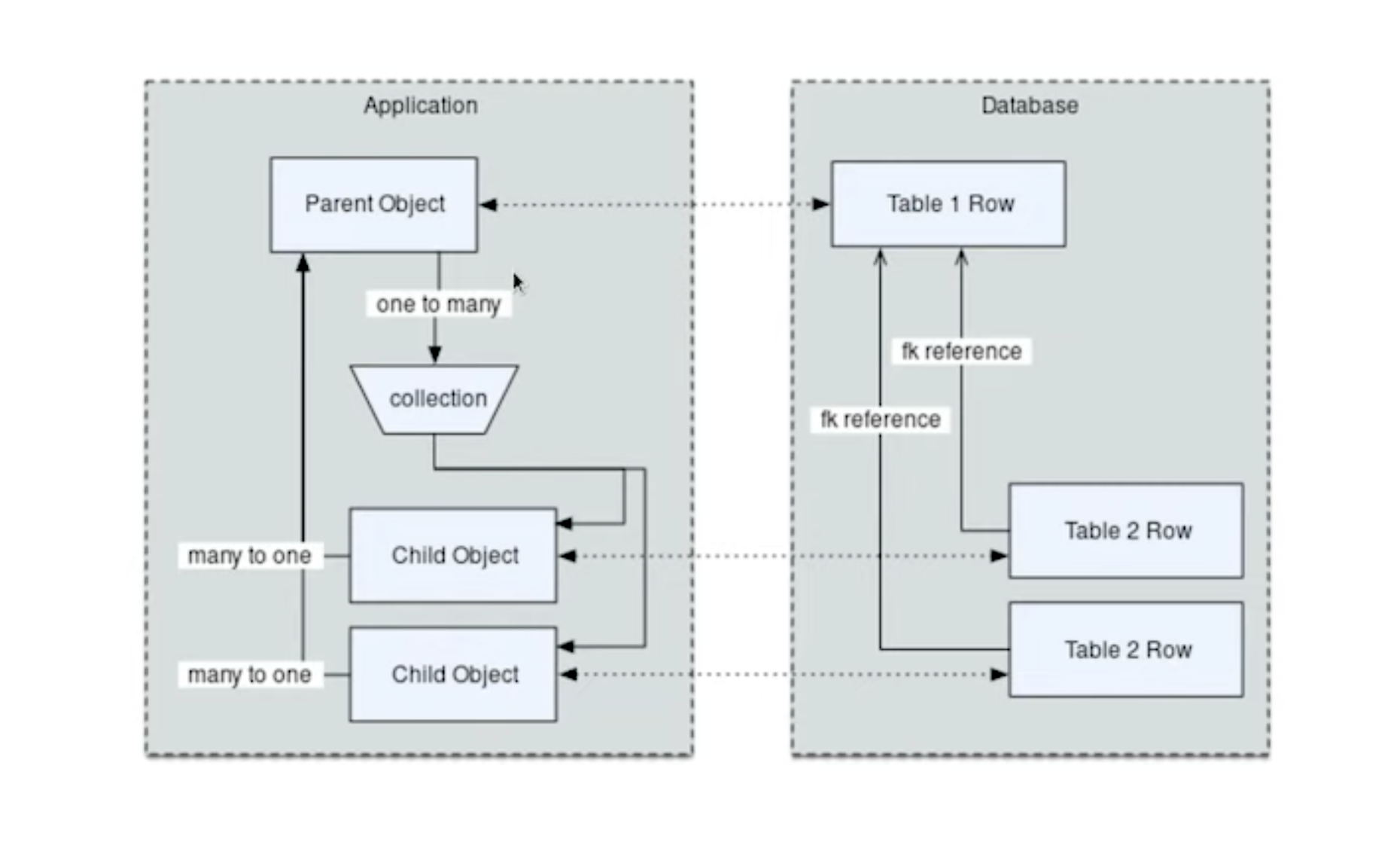

ORM represents basic compositions: one-to-many, many-to-one using foreign key

ORM allows to querying the database in terms of the domain model structure

Some ORM can represent class inheritance hierarchies using variety of schemes

Some ORMs can handle 'sharding' of data, i.e. storing a domain model across multiple schemas or databases

Provide various patterns for concurrency, including row versioning

Provide patterns for data validation and coercion

Source: [1]

8.15.1. Flavors

Active Record or Data Mapper

Declarative or Imperative style configuration

8.15.2. Active Record

Active Record has domain objects handle their own persistence

Every object is a row in a table

Notion of objects working in a transaction is a secondary notion

Create an object:

>>> #

... mark = Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney')

... mark.save()

Usage:

>>> #

... mark = User.query(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney').fetch()

... mark.firstname = 'Melissa'

... mark.lastname = 'Lewis'

... mark.save()

8.15.3. Data Mapper

Tries to keep the details of persistence separate from the object being persisted

It is more explicit

Does not use globals and threaded locals

Always create connection, transaction and explicitly say when to commit

Create an object:

>>> #

... with Session.begin() as session:

... mark = Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney')

... session.add(astro)

Usage:

>>> #

... query = (

... select(Astronaut).

... where(Astronaut.firstname == 'Mark').

... where(Astronaut.lastname == 'Watney').

... scalars().

... first())

...

... with Session.begin() as session:

... astro = session.execute()

... astro.firstname = 'Melissa'

... astro.lastname = 'Lewis'

8.15.4. Declarative Style Configuration

Classes and attributes

Attributes names columns in a database

ORMs may also provide different configuration patterns. Most use an 'all-at-once' style where class and table information is together. SQLAlchemy calls this declarative style [1].

>>> #

... class Astronaut(Base):

... __tablename__ = 'astronaut'

... id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

... firstname = Column(String(length=100))

... lastname = Column(String(length=100))

...

...

... class Mission(Base):

... __tablename__ = 'mission'

... id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

... astronaut_id = Column(ForeignKey('astronaut.id'))

... year = Column(Integer, nullable=False)

... name = Column(String(length=50), nullable=False)

8.15.5. Imperative Style Configuration

There was a plan to remove Imperative Style from SQLAlchemy 2.0, but stayed

The class is not completely agnostic, because mapper heavily influence design

This other way is to keep the declaration of domain model and table metadata separate. SQLAlchemy calls this imperative style [1].

Class is declared without any awareness of database:

>>> #

... class Astronaut:

... def __init__(self, firstname, lastname):

... self.firstname = firstname

... self.lastname = lastname

Then it is associated with a database table:

>>> #

... registry.mapper(

... Astronaut,

... Table('astronaut', metadata,

... Column('id', Integer, primary_key=True),

... Column('firstname', String(50)),

... Column('lastname', String(50)),

... )

... )

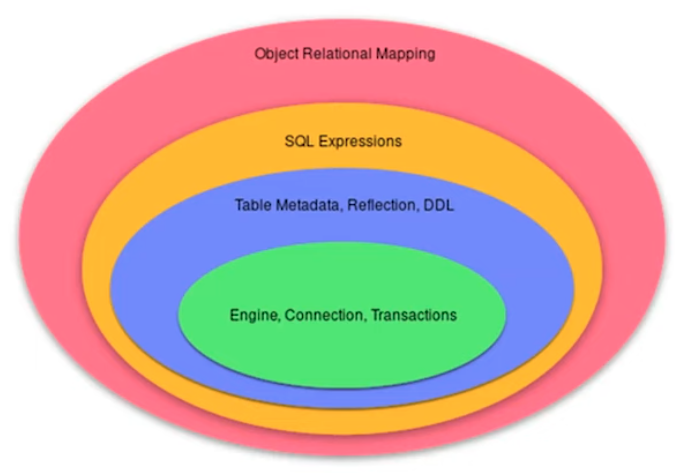

8.15.6. SQLAlchemy ORM

SQLAlchemy ORM is essentially a data mapper style ORM

Most users use declarative configuration style

Imperative style and a range of variants in between are supported as well

Extends SQLAlchemy Core, in particular extending the SQL Expression language

Designed to work with domain classes as well as table constructs

Key features: Unit of Work, Identity Map, Lazy / Eager loading

Unit of Work - accumulates INSERT/UPDATE/DELETE statements and transparently sends it to the database in batch

Identity Map - objects are kept unique in memory based on their primary key identity

Lazy / Eager loading - related attributes and collections can be loaded either on-demand (lazy) or upfront (eager)

Source: [1]

8.15.7. ORM

SQLAlchemy mappings in 1.4/2.0 start with a central object known as 'registry'

Has a collection of metadata inside it

Traditional Declarative Base uses Python metaclass

This gets in a way, when you want to uses metaclass on your own

In such case you can use mapper registry decorator

Using the registry, we can map classes in various ways, below illustrated

using its 'mapped' decorator. In this form, we arrange class attributes in

terms of Column objects to be mapped to a Table, which is named based

on attribute __tablename__ [1].

First create an instance of a Mapper Registry object:

>>> from sqlalchemy.orm import registry

>>>

>>> mapper_registry = registry()

The Mapper object mediates the relationship between model and a Table

object. This mapper is generally behind the scence and accessible.

Then specify the class using mapper registry decorator:

>>> from sqlalchemy import Column, Integer, String

>>> from sqlalchemy.orm import registry

>>>

>>>

>>> Models = registry()

>>>

>>> @Models.mapped

... class Astronaut:

... __tablename__ = 'astronaut'

... id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

... firstname = Column(String(length=100))

... lastname = Column(String(length=100))

...

... def __repr__(self):

... firstname = self.firstname

... lastname = self.lastname

... return f'Astronaut({firstname=}, {lastname=})'

The Astronaut class has now a Table object associated with it.

>>> Astronaut.__table__

Table('astronaut', MetaData(), Column('id', Integer(), table=<astronaut>, primary_key=True, nullable=False), Column('firstname', String(length=100), table=<astronaut>), Column('lastname', String(length=100), table=<astronaut>), schema=None)

>>> from sqlalchemy import select

>>>

>>>

>>> query = select(Astronaut)

>>>

>>> print(query)

SELECT astronaut.id, astronaut.firstname, astronaut.lastname

FROM astronaut

If you do not specify the constructor, it will be automatically generated

for you based on the attributes (id, firstname, lastname) making them

an optional keyword parameters. All parameters are optional, because some of

them can be autogenerated, for example: id [1].

>>> astro = Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney')

>>> astro

Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney')

Using our registry (Models), we can create a database schema for this

class using a MetaData object that is path of the registry:

>>> from sqlalchemy import create_engine

>>>

>>>

>>> engine = create_engine('sqlite:///:memory:')

>>>

>>> with engine.begin() as db:

... Models.metadata.create_all(db)

To persists and load Astronaut objects from the database, we use a

Session object, illustrated here from a factory called sessionmaker.

The Session objects makes use of a connection factory (i.e. an Engine)

and will handle the job of connecting, committing and releasing connections

to this engine. Flag future=True in SQLAlchemy 1.4 will turn on 2.0

compatibility mode. This behavior will be default in 2.0 and flag will be

deprecated.

>>> from sqlalchemy.orm import sessionmaker

>>>

>>>

>>> Session = sessionmaker(bind=engine, future=True)

>>> session = Session()

Creating a session does not implies connection. This is done lazily and will simply create an object and do nothing. Sessions will always delay database connection to the last possible moment, but it will also ensure that this will eventually happen.

8.15.8. Object Statuses

Transient - object created, but not yet added to the session

Pending - object added to a session but not yet stored in database

Persistent - represent an active row in a database (object is stored)

Detached

Pending Delete

8.15.9. Adding Objects

Let's create an transient object (object not yet added to the session):

>>> mark = Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney')

New objects are placed into the Session using add()

>>> session.add(mark)

This did not modify the database, however the object is now known as 'pending'.

We can see the 'pending' objects by looking at the session.new attribute.

>>> session.new

IdentitySet([Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney')])

We can now query for this 'pending' row, by emitting a SELECT statement

that will refer to Astronaut entities. This will first autoflush the

pending changes, then SELECT the row we requested.

>>> from sqlalchemy import select

>>>

>>>

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut).

... where(firstname=='Mark'))

>>>

>>> result = session.execute(query)

Session will autoflush before making queries, that is it will store all the

pending objects before querying it. Session will delay this to the last

possible moment. You can turn this behavior off by specifying a keyword

argument autoflush=False to the sessionmaker factory.

We can get the data back from the result, in this case using the .scalar()

method which will return the first column of the first row.

>>> mark = result.scalar()

>>> mark

Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney')

The Astronaut object we've inserted now has a value for .id attribute.

>>> mark.id

1

The Session maintains a 'unique' object per identity. So astro and

mark are the same object.

>>> mark is astro

True

Identity Map - if you query the database table for the object with for example

id==1 you will get the same object every time, as long as this object is

in the memory. We can look at it on the Session.

>>> session.identity_map.items()

[((__main__.Astronaut, (1,), None), Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney'))]

8.15.10. Making Changes

Add more objects to be pending for flush

.add_all()is the same as.add(), but adds a list of objects

>>> session.add_all([

... Astronaut(firstname='Melissa', lastname='Lewis'),

... Astronaut(firstname='Rick', lastname='Martinez'),

... ])

Modify astro - the object is now described as 'dirty'

>>> astro.firstname = 'Alex'

>>> astro.lastname = 'Vogel'

Nothing changed and no actions were performed to the database yet. If you inspect database current transactions you will have an open transaction process currently in progress.

The Session can us which objects are dirty:

>>> session.dirty

IdentitySet([Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel')])

And can also tell us which objects are pending:

>>> session.new

IdentitySet([Astronaut(firstname='Melissa', lastname='Lewis'), Astronaut(firstname='Rick', lastname='Martinez')])

The whole transaction is committed. Commit always triggers a final flush of

remaining changes. Commit will expire objects. This is due to the fact, that

as soon as data is out there (in database), some other transactions could

have already change the data. You can change this behavior by setting the

expire_on_commit=False parameter to the sessionmaker factory.

>>> session.commit()

After a commit, there's no transaction. The Session 'invalidates' all

data, so that accessing them will automatically start a 'new' transaction

and re-load from the database. This is our first example of the ORM 'lazy

loading' pattern.

>>> astro.firstname

8.15.11. Rolling Back Changes

Make another 'dirty' change, and another 'pending' change, that we might change or minds about.

>>> astro.firstname = 'Beth'

>>> astro.lastname = 'Johanssen'

>>>

>>> chris = Astronaut(firstname='Chris', lastname='Beck')

>>> session.add(chris)

Run a query, our changes are flushed; results come back.

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut).

... where(Astronaut.firstname.in_(['Beth', 'Chris'])))

>>>

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>> result.all()

Those changes are not yet in the database. The transaction was not committed yet. Therefore if your database will be restarted you will loose those information, unless non-default transaction durability options are set in the database configuration.

But we're inside of a transaction. Roll it back:

>>> session.rollback()

All updates and inserts are gone, and all pending objects are evicted. Again,

the transaction is over, objects are expired. Accessing an attribute refreshes

the object and the astro firstname is gone [1].

>>> astro in session

False

And the data is gone from database too.

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut).

... where(Astronaut.firstname.in_(['Beth', 'Chris'])))

>>>

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>> result.all()

[]

8.15.12. ORM Querying

The attributes on our mapped classes act like Column objects, and produce

SQL expressions [1].

>>> expression = (Astronaut.firstname == 'Mark')

>>>

>>> print(expression)

astronaut.firstname = :firstname_1

>>> expression = Astronaut.__table__.c.firstname == 'Mark'

>>>

>>> print(expression)

astronaut.firstname = :firstname_1

Fot the above example, although output is similar, they produce a different objects.

When ORM-specific expressions are used with select(), the Select

construct itself takes an ORM-enabled features, the most basic of which is

that it can discern between selecting from 'columns' vs. 'entities'. Below

the SELECT is to return rows that contain a single element, which would

be an instance of Astronaut. This is translated from the actual SELECT

sent to the database that SELECTs for the individual columns of the

Astronaut entity [1].

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut).

... where(Astronaut.firstname == 'Mark').

... order_by(Astronaut.id))

Introspection:

>>> query._raw_columns[0]

Table('astronaut', MetaData(), Column('id', Integer(), table=<astronaut>, primary_key=True, nullable=False), Column('firstname', String(length=100), table=<astronaut>), Column('lastname', String(length=100), table=<astronaut>), schema=None)

>>>

>>> query._raw_columns[0]._annotations

immutabledict({'entity_namespace': <Mapper at 0x11bc942b0; Astronaut>, 'parententity': <Mapper at 0x...; Astronaut>, 'parentmapper': <Mapper at 0x...; Astronaut>})

The rows we get back from Session.execute() then contain Astronaut

objects as the first element in each row [1].

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>>

>>> for row in result:

... print(row)

...

(Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney'),)

As it is typically convenient for rows that only have a single element to be

delivered as the element alone, we can use the .scalars() method of

Result as we did earlier to return just the first column of each row

[1].

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>>

>>> for row in result.scalars():

... print(row)

...

Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney')

We can also qualify the rows we want to get back with methods like .one()

[1]:

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>> mark = result.scalars().one()

>>>

>>> print(astro)

Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney')

An ORM query can make use of any combination of columns and entities. To

request the fields of Astronaut separately, we name them separately in the

columns clause [1].

>>> query = select(Astronaut.firstname, Astronaut.lastname)

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>>

>>> for row in result:

... print(f'{row.firstname}, {row.lastname}')

...

Mark, Watney

Melissa, Lewis

Rick, Martinez

>>> query = select(Astronaut.firstname, Astronaut.lastname)

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>>

>>> for firstname, lastname in result:

... print(f'{firstname=}, {lastname=}')

...

firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney'

firstname='Melissa', lastname='Lewis'

firstname='Rick', lastname='Martinez'

You can combine 'entities' and columns together:

>>> query = select(Astronaut, Astronaut.firstname)

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>>

>>> for row in result:

... print(f'{row.Astronaut.id}, {row.firstname}, {row.Astronaut.lastname}')

...

1, Mark, Watney

2, Melissa, Lewis

3, Rick, Martinez

The WHERE clause is either by .filter_by(), which is convenient:

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut.firstname, Astronaut.lastname).

... filter_by(firstname='Mark'))

>>>

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>>

>>> for firstname, lastname in result:

... print(f'{firstname=}, {lastname=}')

...

firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney'

Or where() for more explicitness:

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut).

... where(Astronaut.firstname == 'Mark').

... where(Astronaut.lastname == 'Watney'))

>>>

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>>

>>> for row in result.scalars():

... print(f'{firstname=}, {lastname=}')

...

firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney'

8.15.13. Relationships, Joins

Start with the same mapping as before. Except we will also give it a one-to-many relationship to a second entity.

>>> from sqlalchemy import ForeignKey, Column, Integer, String

>>> from sqlalchemy.orm import registry, relationship

>>>

>>>

>>> Models = registry()

>>>

>>> @Models.mapped

... class Astronaut:

... __tablename__ = 'astronaut'

... id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

... firstname = Column(String(length=100))

... lastname = Column(String(length=100))

... missions = relationship('Mission', back_populates='astronaut')

...

... def __repr__(self):

... firstname = self.firstname

... lastname = self.lastname

... return f'Astronaut({firstname=}, {lastname=})'

>>>

>>>

>>> @Models.mapped

... class Mission:

... __tablename__ = 'mission'

... id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

... astronaut_id = Column(ForeignKey('astronaut.id'))

... year = Column(Integer, nullable=False)

... name = Column(String(length=50), nullable=False)

... astronaut = relationship('Astronaut', back_populates='missions')

...

... def __repr__(self):

... year = self.year

... name = self.name

... return f'Mission({year=}, {name=})'

For the other end of one-to-many, create another mapped class with a

ForeignKey referring back to Astronaut. ForeignKey field is a

SQLAlchemy core's thing and relationship field is for ORM's. Note, that

it is not needed to specify type of the relationship (one-to-many, many-to-one,

or many-to-many) as of relationship() will infer this by the column type

(ForeignKey -> one-to-many) [1].

Create tables

>>> from sqlalchemy import create_engine

>>>

>>>

>>> engine = create_engine('sqlite:///:memory:')

>>>

>>> with engine.begin() as db:

... Models.metadata.create_all(db)

Will produce:

BEGIN

PRAGMA main.table_info("astronaut")

PRAGMA temp.table_info("astronaut")

PRAGMA main.table_info("mission")

PRAGMA temp.table_info("mission")

CREATE TABLE astronaut (

id INTEGER NOT NULL,

firstname VARCHAR(100),

lastname VARCHAR(100),

PRIMARY KEY (id)

)

CREATE TABLE mission (

id INTEGER NOT NULL,

astronaut_id INTEGER,

year INTEGER NOT NULL,

name VARCHAR(50) NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (id),

FOREIGN KEY(astronaut_id) REFERENCES astronaut (id)

)

COMMIT

Insert data in the Astronaut table. Here we illustrate the sessionmaker

factory as a transactional context manager [1]:

>>> from sqlalchemy.orm import sessionmaker

>>>

>>>

>>> Session = sessionmaker(bind=engine, future=True)

>>>

>>> with Session.begin() as session:

... session.add_all([

... Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney'),

... Astronaut(firstname='Melissa', lastname='Lewis'),

... Astronaut(firstname='Rick', lastname='Martinez'),

... ])

1.4/2.0 tries to make more consistent. Session.begin() is analogous to

Engine.begin(). Sessionmaker is analogous to core engine. And the session

itself is analogous to core connection.

A new Astronaut object also gains an empty missions collection now.

>>> alex = Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel')

>>> alex.missions

[]

Populate this collection with new Address objects.

>>> alex.missions = [

... Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1'),

... Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3'),

... ]

'Back populates' sets up Mission.astronaut for each Astronaut.mission

>>> alex

Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel')

>>>

>>> alex.missions

[Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1'), Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3')]

>>>

>>> alex.missions[0]

Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1')

>>>

>>> alex.missions[0].astronaut

Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel')

You can specify the relation only in one way, but usually people will do it both-ways for easy of use.

Adding alex will 'cascade' each Astronaut into the Session as well.

>>> session = Session()

>>> session.add(alex)

>>> session.new

IdentitySet([Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel'), Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1'), Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3')])

Now we commit the changes to the database.

>>> session.commit()

ORM must know which object goes first, and then it uses its id to fill

the ForeignKey fields of related objects. SQLAlchemy does that

automatically.

After expiration, alex.missions emits a 'lazy load' when first accessed:

>>> alex.missions

[Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1'), Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3')]

The collection stays in memory until the transaction ends.

>>> alex.missions

[Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1'), Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3')]

Collections and references are updated by manipulating objects themselves; setting up of foreign key column values is handled automatically.

>>> from sqlalchemy import select

>>>

>>>

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut).

... filter_by(firstname='Mark'))

>>>

>>> mark = session.execute(query).scalar_one()

>>> alex.missions

[Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1'), Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3')]

>>>

>>> mark.missions

[]

>>> alex.missions[1].astronaut = mark

>>>

>>> alex.missions

[Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1')]

>>>

>>> mark.missions

[Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3')]

By assigning .astronaut on one of the alex missions, the object moved

from one missions collection to the other. This is the back populates

feature at work.

8.15.14. Querying with Multiple Tables

A SELECT statement can select from multiple entities simultaneously.

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut, Mission).

... where(Astronaut.id == Mission.astronaut_id))

>>>

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>>

>>> for row in result:

... print(row)

...

(Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel'), Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1'))

(Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney'), Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3'))

Or unpack the results. We know that there will be two objects in a tuple

because we did select(Astronaut, Mission).

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut, Mission).

... where(Astronaut.id == Mission.astronaut_id))

>>>

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>>

>>> for astronaut, mission in result:

... print(f'{astronaut=}, {mission=}')

...

astronaut=Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel'), mission=Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1')

astronaut=Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney'), mission=Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3')

As is the same case in Core, we use the select().join() method

to create joins. An entity can be given as the target which will join along

foreign keys.

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut, Mission).

... join(Mission))

>>>

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>>

>>> result.all()

[(Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel'), Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1')),

(Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney'), Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3'))]

Or you can give it an explicit SQL expression for the ON clause.

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut, Mission).

... join(Mission, Astronaut.id == Mission.astronaut_id))

>>>

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>>

>>> result.all()

[(Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel'), Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1')),

(Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney'), Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3'))]

However the most accurate and succinct way is to use the relationship-bound attribute.

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut, Mission).

... join(Astronaut.missions))

>>>

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>>

>>> result.all()

[(Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel'), Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1')),

(Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney'), Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3'))]

All three methods should result the same data.

Note, that join(Astronaut.missions) is only available in ORM, because

missions attributes is an ORM relationship.

>>> print(query)

SELECT astronaut.id, astronaut.firstname, astronaut.lastname, mission.id AS id_1, mission.astronaut_id, mission.year, mission.name

FROM astronaut JOIN mission ON astronaut.id = mission.astronaut_id

The ORM version of table.alias() is to use the aliased() function on

mapped entity.

>>> from sqlalchemy.orm import aliased

>>>

>>>

>>> m1 = aliased(Mission)

>>> m2 = aliased(Mission)

>>>

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut).

... join_from(Astronaut, m1).

... join_from(Astronaut, m2).

... where(m1.name == 'Ares1').

... where(m2.name == 'Ares3'))

>>>

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>> result.all()

[(Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel'),)]

>>> print(query)

SELECT astronaut.id, astronaut.firstname, astronaut.lastname

FROM astronaut JOIN mission AS mission_1 ON astronaut.id = mission_1.astronaut_id JOIN mission AS mission_2 ON astronaut.id = mission_2.astronaut_id

WHERE mission_1.name = :name_1 AND mission_2.name = :name_2

To join() to an aliased() object with more specificity, a form such

Class.relationship.of_type(aliased) may be used:

>>> from sqlalchemy.orm import aliased

>>>

>>>

>>> m1 = aliased(Mission)

>>> m2 = aliased(Mission)

>>>

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut).

... join(Astronaut.missions.of_type(m1)).

... join(Astronaut.missions.of_type(m2)).

... where(m1.name == 'Ares1').

... where(m2.name == 'Ares3'))

>>>

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>> result.all()

[(Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel'),)]

Useful for querying objects which has special conditions, such as:

is_deleted=False flag, or newer than particular date.

As was the case with Core, we can use subqueries and joins with ORM

mapped classes as well.

>>> from sqlalchemy import func

>>>

>>>

>>> subquery = (

... select(func.count(Mission.id).label('count'), Mission.astronaut_id).

... group_by(Mission.astronaut_id)

... subquery())

>>>

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut.firstname, func.coalesce(subquery.c.count, 0)).

... outerjoin(subquery, Astronaut.id == subquery.c.astronaut_id))

>>>

>>> result = session.execute(query)

>>> result.all()

[('Mark', 1), ('Melissa', 0), ('Rick', 0), ('Alex', 1)]

CTEs works the same way too.

8.15.15. Eager Loading

The N plus one problem is an ORM issue which refers to the many SELECT

statements emitted when loading collections against a parent result. As

SQLAlchemy is a full featured ORM it has the same problem. This is the biggest

and the most famous problem of the ORM.

Lazy loaded N+one prone code:

>>> query = select(Astronaut)

>>>

>>> with Session() as session:

... result = session.execute(query)

... for astronaut in result.scalars():

... print(astronaut, astronaut.missions)

...

Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney') []

Astronaut(firstname='Melissa', lastname='Lewis') []

Astronaut(firstname='Rick', lastname='Martinez') []

Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel') [Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1'), Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3')]

However, SQLAlchemy was designed from the start to tame the 'N plus one'

problem by implementing 'eager loading'. Eager loading is now very mature,

and the most effective strategy for collections is currently the

selectinload option:

>>> from sqlalchemy.orm import selectinload

>>>

>>>

>>> query = (

... select(Astronaut).

... options(selectinload(Astronaut.missions)))

>>>

>>> with Session() as session:

... result = session.execute(query)

... for astronaut in result.scalars():

... print(astronaut, astronaut.missions)

...

Astronaut(firstname='Mark', lastname='Watney') []

Astronaut(firstname='Melissa', lastname='Lewis') []

Astronaut(firstname='Rick', lastname='Martinez') []

Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel') [Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1'), Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3')]

The oldest eager loading strategy is joinedload(). This uses LEFT OUTER

JOIN or INNER JOIN to load parent + child on one query. joinedload()

can work for collections as well, however it is best tailored towards

many-to-one relationships, particularly those where the foreign key is

NOT NULL.

>>> from sqlalchemy.orm import joinedload

>>>

>>>

>>> query = (

... select(Mission).

... options(joinedload(Mission.astronaut, innerjoin=True)))

>>>

>>> with Session() as session:

... result = session.execute(query)

... for mission in result.scalars():

... print(mission, mission.astronaut.firstname)

...

Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1') Alex

Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3') Alex

Note, Eager loading 'does not' change the result of the Query. Only how

related collections are loaded. An explicit join() can be mixed with the

joinedload() and they are kept separate.

>>> from sqlalchemy.orm import joinedload

>>>

>>>

>>> query = (

... select(Mission).

... join(Mission.astronaut).

... where(Astronaut.firstname == 'Alex').

... options(joinedload(Mission.astronaut)))

>>>

>>> with Session() as session:

... result = session.execute(query)

... for mission in result.scalars():

... print(mission, mission.astronaut)

Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1') Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel')

Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3') Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel')

To optimize the common case of 'join to many-to-one and also load it on the

object', the contains_eager() option is used

>>> from sqlalchemy.orm import contains_eager

>>>

>>>

>>> query = (

... select(Mission).

... join(Mission.astronaut).

... where(Astronaut.firstname == 'Alex').

... options(contains_eager(Mission.astronaut)))

>>>

>>> with Session() as session:

... result = session.execute(query)

... for mission in result.scalars():

... print(mission, mission.astronaut)

Mission(year=2030, name='Ares1') Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel')

Mission(year=2035, name='Ares3') Astronaut(firstname='Alex', lastname='Vogel')